It All Means Something

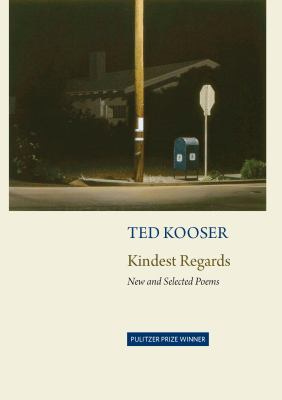

Kindest Regards: New and Selected Poems | Ted Kooser | Copper Canyon Press

Reviewed by Christian Leithart

Ted Kooser’s latest collection of poems, published in 2018 by Copper Canyon Press, begins with an epigraph, a quote from Stanley Kunitz: “It is out of the dailiness of life that one is driven into the deepest recesses of the self.” If there is one common thread that weaves the poems in Kooser’s collection together, it is that phrase, “the dailiness of life.” Flights of fancy and linguistic tricks hold no interest for Kooser (no puns here). He does not muse on politics or the fate of the human race. He writes about what is within arm’s reach. Very little happens that you would not recognize from your own workaday existence.

The title of the book brings to mind a letter from an old friend, and old friends drop in repeatedly throughout the pages. Even the poems that are written as present observation remind Kooser of things past: “the night when each of us remembers something / snowier” (First Snow, p. 6); “Black streak across the centerline, / all highways make me think of you” (For a Friend, p. 19). Past and present meet, sometimes recognizing one another, sometimes greeting one another with caution. “The Great-Grandparents” (p. 77) describes meeting one’s ancestors, with their odd clothes and funny smells, dropped in from another world. Ages past are another world, one that is mixed with the present, impossible to disentangle.

The loss of the past—and the feeling of missing it—is the source of much of Kooser’s poetry. But loss isn’t the whole story. Kooser’s playfulness is on display in “Barn Owl” and “Song of the Ironing Board” (p. 126-27): “On stiffening legs I suffered / the steam iron’s hot incontinence.” “At the Bait Stand” and “The Widow Lester” (pp. 22-23) present two short pictures of humanity’s quirks, benign and poisonous. “Arabesque” (p. 212) is another example of the same, depicting the dance of a garbage man stepping on and off the back of his truck to “the wild applause of a thousand flies.” “The Urine Specimen” (p. 45) is an ironic presentation of the indignity of being a human: “You lift the chalice and toast / the long life of your friend there in the mirror, / who wanly smiles, but does not drink to you.”

Like Solomon, Kooser learns wisdom by watching the natural world (“How to Foretell a Change in the Weather” p. 13). He’s endlessly fascinated by the tiny wonders around him (“Daddy Longlegs” p. 34; “Shoes” p. 65) and describes them piece by piece, as though he is sketching a picture while you watch (“Old Dog in March” p. 75; “A Jar of Buttons” p. 113). A woman pushing a wheelchair is a pianist striking the keys (p. 108). A round hay bale is “all shoulders” (p. 86).

Again following Solomon, Kooser sees that life holds inevitable and inexplicable trouble. As often as he notices tiny wonders, he sees danger, death, frustration. He does not rant against them. A pained glance, a tired shrug, is enough. After describing an abandoned farmhouse, he sums up the scene with “Something went wrong, they say” (p. 21). Pain and beauty often walk hand-in-hand, as in “Cleaning a Bass” (p. 41). The trick to coping is knowing where to look. Watching a swallow return to its nest, Kooser remarks that “the world is alive / with such innocent progress.” (p. 40) In “Mother” (p. 111) the repetition of nature is one of the great comforts of life, something solid to hold onto: “Those same / two geese have come to the pond again this year, / honking in over the trees and splashing down.” In the same poem, Kooser describes this attention as something he learned from his mother: “Were it not for the way you taught me to look / at the world, to see the life at play in everything, / I would have to be lonely forever” (p. 112).

Kooser hones in on the remains of things, like an archaeologist combing through layers of time. Broken-down trucks. Unused shears. Tree stumps. Ashes. He is especially fascinated by old tools. “Lantern” (p. 143) ruminates on an aged lantern that, even in its prime, gave “not more than a cup of warmth.” At the end of its usefulness, it provides a bed for a brood of mice. They soon abandon it, “the way we all, one day, move on / leaving a sharp little whiff / of ourselves in the dirty bedding.” In Kooser’s eyes, we are no more or less significant than mice. Our only advantage is the ability to write verses about our brief passage. Images and stories illuminate the short, dark path: “Theirs are the open wings / we light our table by” (“At a Kitchen Table” p. 146).

With death looming over every page, writing seems for Kooser to be a spiritual exercise. Graveyards and churches are sprinkled through the book. Often, the formal signs of religion give way to informal, natural spirituality. In “The Red Wing Church” (p 24), a church is dismantled and used to prop up the rest of the town. As Kooser says, “The good works of the Lord are all around.” Notably absent is the cross from the steeple roof. It may be easy to sense divine presence in the world, but salvation is harder to come by: “The cross is only God knows where.” In yet another poem about watching birds, Kooser uses the vivid metaphor of a burning church, “charred pages of hymnals settling through smoke,” and ascribes this image to “a darkness feeding in me” (“Five Finger Exercise” p. 73). The beauty and the pain resurface. Speaking of them is the only fitting response.

The presence of God in nature is displayed again in “Locust Trees in Late May,” which scatter oblong leaves all over the ground. Kooser compares them to the rolled pennies he and his friends would get at the carnival, each with the Lord’s Prayer pressed into its face. “Each of us / got only one, but these trees give many” (p. 160). God does not speak in the book, but His presence is felt. You get the sense that Kooser’s religious position is one of humility. He is aware of his tinyness. In “Nine Wild Turkeys” (p. 164), human beings become turkeys crossing a country road, while God watches from His truck, amused and patient.

Seeing the world’s decay, and feeling it himself, Kooser is not sure what to hope for. Paying attention to the little details and comparisons around him gives him some assurance that it all means something.“I want to be better at carrying sorrow,” he says in “New Moon” (p. 153). The arrangement of words gives his life the illumination that he seeks. In his excellent craft book, The Poetry Home Repair Manual, Kooser says, “By writing poetry, even those poems that fail and fail miserably, we honor and affirm life. We say “We loved the earth but could not stay” (5).

He expresses again his own inadequacy to the task of giving meaning to life in “Awakening,” in which he describes himself waking up with the metaphor of carrying a bucket: “a weighty thing / like life itself, in which you dip / the leaky cup of your hands / and drink.” (p. 155) Even when the words aren’t up to the task, the sheer act of writing and paying attention is enough. “This is my life,” he says in “A Morning in Early Spring (p. 150), “none other like this.”

The full expression of this acceptance comes in “Deep Winter” (p. 152). Kooser finds himself alone behind a shed, looking out at the snowy fields. He feels the presence of older generations around him, those who have also looked for “something to use to prop / up something else.” The words slip through his fingers. But as he stands among those other lost observers, he feels that they, every one of them, is “a piece of some great, rusty work / we seem to fit exactly.”

Christian Leithart writes and teaches in Birmingham, Alabama. He likes old books and staring out the window.

If you enjoyed this review, be sure to subscribe to the quarterly print edition of FORMA Journal. And don’t miss the most recent episodes of the Forma Podcast.