Knowing the Worst

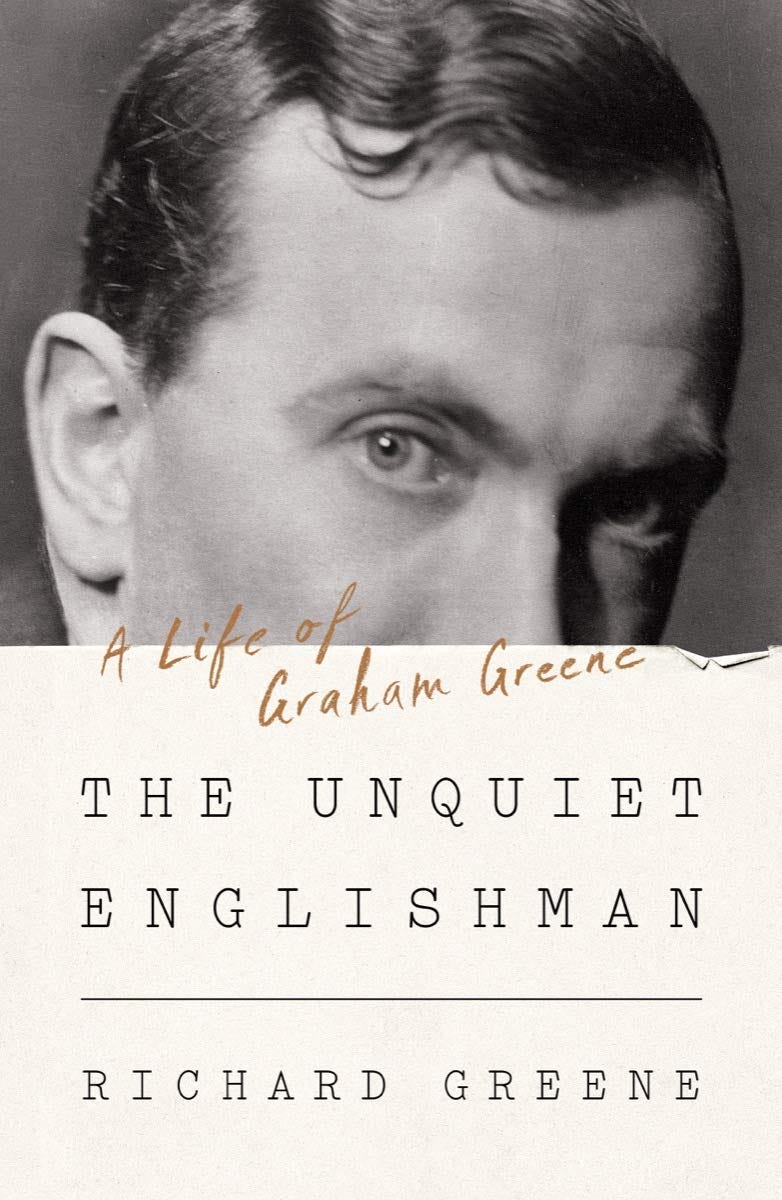

The Unquiet Englishman: A Life of Graham Greene | Richard Greene | W. W. Norton & Company

This review appears in the forthcoming summer edition of FORMA to which you can subscribe now. Other essays include a piece by James Matthew Wilson on poetry and the moral imagination, Emily Andrews on Tolstoy’s view of literary criticism, David Russell Mosley on the medieval cosmos, and more. This week is your last chance to subscribe!

Named not by the author but by his readers, “Greeneland” is the darker, more desperate reflection of our own world in which many of Graham Greene’s novels are set. Anyone who has ever set foot there will know it again at once. It feels like a Charles Dickens novel minus the children, wealthy philanthropists, and general optimism—a world dominated by what Greene himself once called “the Fagan darkness.” I have spent so much time there that even the faintest whiff of Greeneland can set my pulse racing—I am overcome with images of hunted men, beleaguered priests, foreign locales, and Carol Reed movies. It is also the very last atmosphere I want to encounter in a biography of Greene. Measuring by this standard alone, Richard Greene’s The Unquiet Englishman is the best to come forth in some time.

Any biography that invokes a world crafted by Graham Greene is a biography too much in the shadow of the man himself. Some accounts of his life fall prey to this for the rather excusable reason that they are literally of Greene’s own making. A Sort of Life and Ways of Escape are probing, as autobiographies go, but pointedly selective. Not that Greene spared the lurid details—his then-fascination with Freudian psychoanalysis prompted surprising candor about private matters, even of a sexual nature, in A Sort of Life. Yet he was extremely protective of details surrounding his increasingly unhappy marriage and the religious conversion that had accompanied it—much to the frustration of his Catholic readers.

When Greene (feeling pressure to let someone else tell his story) selected Norman Sherry to write his “official” biography, it was largely on the strength of Sherry’s promise “to keep away from the personal . . . but if the work begins to move in a biographical direction you will be free to censor it.” Sherry’s first volume is not quite as discrete as he promised, but Greene’s shadow hovers over the entire project.

Greene’s concerns for privacy anticipated a prurient interest in his personal life, and his fears were confirmed when the unofficial biographies began appearing. Some early books about Greene were little better than tabloids in their preoccupation with his romantic entanglements, and even the more serious studies could get bogged down in looking for correspondences between Greene’s love life and his fiction. This temptation seems forgivable when the subject, Greene, made a career writing spy thrillers and dramas revolving around love affairs. And yet, while a fictional life might be justly reduced to its most sensational details, the same is rarely true of a genuine human existence.

Richard Greene (who probably has the phrase “no relation” printed on his business cards by now) takes this truth as his polestar and wastes no time announcing the fact:

Even as this biography narrates, with much new detail, the key events and patterns in his private life, it swings the balance away from obscure details of his sexual life, which have captivated earlier biographers, to an account of his engagement with the political, literary, intellectual, and religious currents of his time.

The “new detail” comes courtesy of several memoirs by people close to the author, as well as troves of letters, discovered or published since the last serious attempt at a Greene biography. There were no better hands for these new materials to fall into than Richard Greene’s. As editor of Graham Greene: A Life in Letters (2008), he is already deeply familiar with Greene the author, and the supremely valuable practice of aggregating a myriad of fragmentary sources and synthesizing from them a comprehensive and coherent narrative of a life. Of course, any biographer can adopt such a method, but in Richard Greene the practice rises to the level of instinct, sometimes leading him to valuable material far removed from the writings or affairs of the primary subject and serving him well in his project of presenting a balanced, whole (Graham) Greene.

One of the more gratifying fruits of the biographer’s method is, at last, a happy conclusion to a notorious episode in the author’s life—the Shirley Temple libel case. Long before he was an Oscar-nominated screenwriter, young Graham Greene was paying the bills by writing movie reviews. He hadn’t been at it for long when he was slapped with a lawsuit over his review of (wait for it) Wee Willie Winkie. In the review, Greene accused the studio behind the film of exploiting the child actress in order to appeal to adult male audiences with prurient tastes. Though the slander was not against Temple per se, her lawyers jumped at the chance to sue Greene for libel and eventually won after an acrimonious and very public court battle.

When Temple met the aging Greene decades later, well into her celebrated career with the U.S. foreign service, they quickly became friends. Drawing from memoirs she wrote shortly after that period, Richard Greene suggests one basis for the easy friendship was that her own recollection corroborated Greene’s “view of the studios as full of sexual menace for child actors.” In that light, the early episode—sometimes attributed to the brash pen of a young writer—can be better understood as one of Greene’s early forays into the humanitarian arenas where he would spend most of his adult life.

Admittedly, Greene is a bit like the famous lovers in Dante’s second circle, blown about by the wind of unfettered affections. Richard Greene advocates, though, for a charitable reading of the novelist as a man in the grips of some form of bipolarity—a disorder better understood today than it was even at the end of Greene’s life. While “journalists looking for easy copy have sometimes condemned Graham Greene’s character,” he suggests “the disasters, especially of his marriage and sexual life, are generally more pitiable than culpable.” He does not contend that culpability should give way entirely to pity (the novelist himself had little patience for the kind of pity that distorted reality) but does want the writer’s detractors to recognize that his sins brought him more pain than pleasure. “Indeed,” he adds, referring to Graham Greene’s professional and personal preoccupation with suicide, “his survival itself is something of a triumph.”

The Unquiet Englishman does more than its predecessors to show that Graham Greene’s vices and virtues share a single source. The heedless affections that led him into adultery also led him into the thick of the twentieth century’s worst humanitarian crises with little concern for his own safety. These affections, and the ferocious loyalty that often undergirded them, can be summed up in Greene’s own concept of involvement. “Greene used the term ‘involvement’ to describe a kind of loyalty, passion, and commitment that can overtake a person who observes suffering and injustice—as a character remarks in The Quiet American, ‘Sooner or later, one has to take sides. If one is to remain human.’”

Greene dodged Haitian hit squads, ducked gunfire on Vietnam battlefields, and rode a donkey across the worst wastelands of Mexico because of an insuperable instinct to “take sides.” In the cases of the Marxist revolution in Mexico and the Spanish Civil War—two upheavals that saw the progressive parties brutally oppressing Catholics—he had to take sides against those parties with which his own liberal politics would formally have aligned him. It is a mark of his integrity that no one and nothing commanded more of Greene’s loyalty than the church in which he himself often felt like a “displaced person.”

Richard Greene is to be commended particularly for his affectionate attention to (Graham) Greene’s later years. He offers thoughtful critical treatments of late novels including The Honorary Consul and Greene’s most underrated success, Monsignor Quixote. Quixote is both an inventive retelling of its classic namesake and a tribute to one of the author’s most intimate friendships. In the later decades of his life, Greene began taking yearly trips through Spain with Father Leopoldo Duran, who became his friend and confessor. The complete correspondence of Greene and Duran is among the newly available source material informing this biography. These letters reveal the aging Greene—who had all but excommunicated himself in the heyday of his adulteries, not going to confession or receiving communion for years at a time—as a penitent and unexpectedly pious old man. Each year the pair would visit the ancient Trappist monastery of Oseira, which features prominently in the mystical conclusion of Monsignor Quixote. When he first saw it in 1976, Greene “was impressed by its austerity, and wrote in the guest book: ‘Thank you for these moments of peace and silence. Please pray for me. Graham Greene.’”

One of my favorite literary serendipities is that the Whiskey Priest of The Power and the Glory fails to escape by boat to the city of Vera Cruz (“true cross”), but stumbles instead into martyrdom—the truest cross. Greene’s own end boasts a similarly happy coincidence. When the blood disease that claimed his life entered its final stages, he was admitted to hospital. There the man who had taken Thomas as his baptismal name (in honor of his abiding doubt) received communion and last rites before finally succumbing on April 3, 1991. The hospital’s name: Hospital de la Providence (“the hospital of providence”).

Richard Greene weaves a complex narrative, to which Graham Greene’s own concept of “involvement” is more integral than any singular besetting sin. He doesn’t whitewash Greene’s failings, and doesn’t ignore the connection between life and art, but also never loses sight of “the central narrative of Graham Greene’s life—how politics, faith, betrayal, love, and exile become great fiction.” Richard Greene brings us to the place described by the pitiable Scoby in The Heart of the Matter: “Here you could love human beings nearly as God loved them, knowing the worst.” Finally, a biographer leaves us knowing the best, too.

Sean Johnson is an associate editor of FORMA. He teaches literature at Veritas Academy in Richmond, VA.