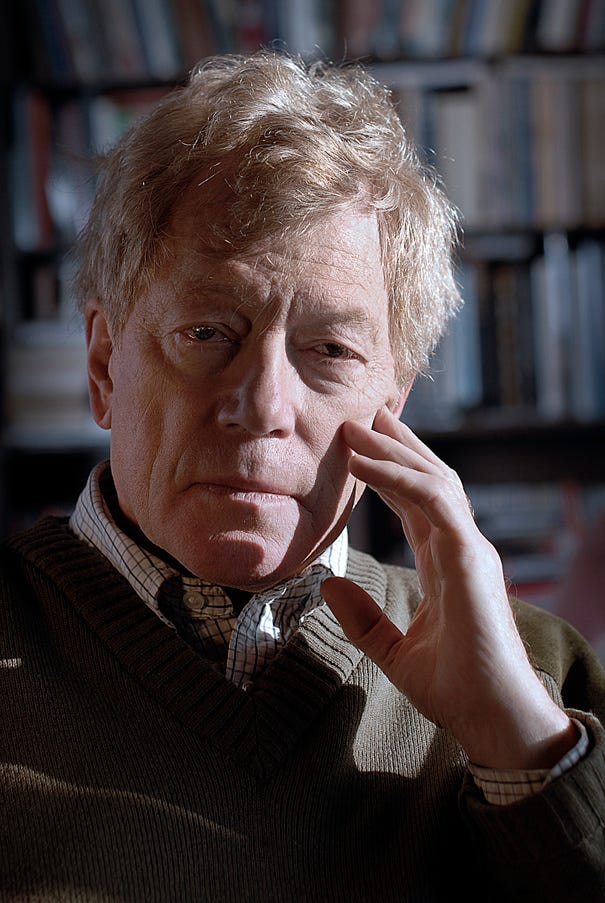

RIP Roger Scruton: Unrevolutionary Renaissance Man

On the enviable life of the preeminent conservative thinker of our age

By Joshua Gibbs

In the age of social media, it is hard to have heroes, or living heroes at any rate. In the last five years, I watched several personal heroes take to Facebook and make grand spectacles of themselves. Having tasted the intoxicating liquor of a widespread and instantaneous response to their most trifling thoughts— a privilege which not even the more powerful Roman emperors or Renaissance popes enjoyed— they rather hastily gave themselves over to personal pageantry. Grandstanding is not an invention of social media, though social media certainly has a profound power to call it out of people, even people who build their careers on the pursuit of virtue and the sober enjoyment of creation.

Given how breathtaking and shocking the work of a public intellectual must now be in order to garner any attention, the popularity and mildness of Roger Scruton were an impressive paradox. On January 12th, 2020, Roger Scruton passed from this life to the next having never tried to advance his career through online ostentation or argumentative peacockery. Given that Scruton stood up for a traditional understanding of art and beauty, readers might have expected his lampooning of hacks like Damien Hirst and Michael Craig-Martin to be more severe, more vicious. However, when Scruton interviewed Craig-Martin in Why Beauty Matters, the most damning (and the most persuasive) response Scruton offered to the conceptual artist’s banal defense of Marcel Duchamp was a quiet and bemused smile, as though he were listening to a teenage boy explain true love. Scruton’s conservatism had a light touch. As all conservatism should.

While Scruton made a name for himself as a conservative thinker, he also wrote about wine, sex, art, architecture, and theories of beauty. He wrote music. He wrote novels. His broad interests were not in spite of his politics, but because of them. In How To Be A Conservative, Scruton wrote:

“Conservatism starts from a sentiment that . . . good things are easily destroyed, but not easily created. This is especially true of the good things that come to us as collective assets: peace, freedom, law, civility, public spirit, the security of property and family life . . . In respect of such things, the work of destruction is quick, easy and exhilarating; the work of creation slow, laborious and dull.”

In other words, Scruton was entirely comfortable with the boring nature of conservative politics.

Conservatives are interested in stability and longevity, neither of which is very sexy. On the other hand, liberal politics is exciting, thrilling. Progressives eat the air, promise-crammed. They are oriented toward the future and forever at war with the past, which they invariably characterize as superstitious, primitive, and ignorant. Of course, the past is everywhere—the present is just sort of an incarnate past—and so the only way forward for progressives is through perpetual, endless revolution. Revolutions are awe-inspiring and spectacular. They occupy the whole interest of the people. Conservatives do not need politics to be sublime and hopeful, though. They have art and religion for that. Scruton had a great diversity of interests because he could. His politics not only allowed it but encouraged it. Because it is born of “a just correspondence and symmetry with the order of the world” and is modeled on “the method of nature,” conservatism sends people out of city hall into the world to observe it. Forests, mountains, lakes, rivers, the beasts of the field, the birds of the air, winter and summer, spring and fall, sun, moon, and stars all have something to teach us, and not just something to teach us about government, but about the good life. Everything need not be reconciled to statecraft, for even statecraft must be reconciled with creation.

Because he never asked more of politics than it could reasonably give, Scruton lived a good life. A cursory glance of Scruton’s bibliography suggests a full life, a rich life, and an enviable one: The Aesthetics of Architecture in 1979; Sexual Desire: A Moral Philosophy of the Erotic in 1986; On Hunting in 1998; Beauty in 2009; I Drink Therefore I Am: A Philosopher’s Guide to Wine in 2009, and nearly fifty other titles, some of which are about politics, many of which are not. In moments of weakness I suppose I have envied the bank accounts of Rush Limbaugh or Sean Hannity, though I don’t think either of those fellows could keep a kitten entertained with a thousand balls of string. They don’t have enviable lives. Look at their oeuvres. They don’t even have enviable minds. Can you imagine Limbaugh writing a book called The Aesthetics of Architecture? Can you imagine Hannity writing a book called Sexual Desire? The very thought of it curls the lower lip. No, no, if you could choose which conservative pundit to come back as, you’d come back as Roger Scruton.

Sadly, most people involved in conservative politics these days haven’t caught on to the fact that conservatism frees people to care about things other than the law. For the new reader who is just coming to Scruton’s work, I would not suggest beginning with his books on politics. Those books are good, of course, but Scruton’s political views are born out of his experience of the world. If you genuinely find politics more interesting than sex, wine, art, and music, Scruton’s not your man. I hope he is, though.

Joshua Gibbs is author of the books How to Be Unlucky: Reflections on the Pursuit of Virtue and Something They Will Not Forget: A Handbook for Classical Teachers, and host of the podcast Proverbial, which you can subscribe to now wherever you listen to podcasts.

If you enjoyed this review, be sure to subscribe to the quarterly print edition of FORMA Journal. The Winter 2020 issue is headed to mailboxes in early February.