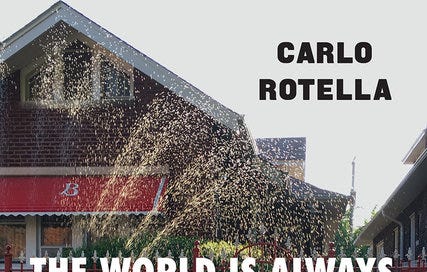

The World Is Always Coming to an End

The World Is Always Coming to an End: Pulling Together and Apart in a Chicago Neighborhood | Carlo Rotella | The University of Chicago Press

Some books take a while to draw you in.

But when I’d finished the first paragraph of Carlo Rotella’s The World Is Always Coming to an End: Pulling Together and Pulling Apart in a Chicago Neighborhood, I knew that I was going to love it:

While working on this book, I got in the daily habit, whenever I was in Chicago, of taking a walk between the two houses in South Shore in which I grew up. One is on the 7100 block of Oglesby, the other on the 6900 block of Euclid. They’re not quite a mile apart, no more than a twenty-minute walk each way, but to go from one to the other is to pass through three distinct worlds. Those worlds, and the resonances and disjunctions between them, give shape to the place that shaped me.

This opening paragraph is preceded by a two-page spread featuring an illustrated street-map of South Shore, to orient readers who (like me) are not intimately familiar with the neighborhood. As for the defining characteristics of those “three distinct worlds” Rotella passed through on his ritual walks, you’ll have to read the book yourself; you’ll find them in the page and a half following, along with an assessment that jibes with many other reports from across these United States: “The middle strata of American society that grew so spectacularly in the postwar era are hollowing out, aging out, contracting, leaving a city of haves and have-nots separated by a deepening divide that makes it hard to see each other as neighbors.” Oh, dear, you may be thinking, this again? But what Rotella offers (as Chris Arnade does, in a very different fashion, in Dignity) is far richer, deeper, and stranger than any routine lamentation over that “deepening divide.”

The arresting title of Rotella’s book turns out to be a quotation drawn from the history of South Shore, not simply a reminder of perennial wisdom, especially timely at a moment when so many people are proclaiming imminent doom. The quotation comes early, on p. 9:

Allan B. Hamilton, a real estate man whose family name used to grace one of those long-defunct movie theaters on 71st Street, once said, “The world is always coming to an end in South Shore.” That was in 1969. South Shore, which had been over 90% white in 1960, would be 70% black by 1970, and over 95% black by 1980. Offering some historical perspective to those inclined to see this change as the end of the world, Hamilton noted that in the past South Shore’s residents of English descent had feared imminent apocalypse when the Irish arrived, as had the Irish when Jews began moving in. Each time, the newcomers failed to destroy the neighborhood . . . In a few more years, though, he would sell off his family’s extensive holdings on 71st Street and join the exodus of white people and their money.

So was Hamilton just kidding himself when he argued for taking the long view? A few years ago, Rotella—who was born in 1964—began revisiting the neighborhood whenever he was back in Chicago, walking the streets, talking with people, taking notes. The result is the best book I’ve ever read about a particular neighborhood and about the very concept it instantiates. “Neighborhood,” Rotella writes, “the first step beyond the household, is the most intimate public stage on which we live the consequences of history.” And there’s more: “it shapes sensibility, your instrument for encountering the world.”

If you like this review, you’ll love what a full subscription gets you: Access to digital versions of the content in our quarterly print journal, plus extra reviews to great books worth noticing. Subscribe now for 50% off!

Even if you don’t read the whole book, you could get a lot simply by reading the introduction, from which I’ve been quoting, where Rotella teases out the ways in which “the term neighborhood can shrink or stretch in scale to fit a small cluster of buildings or an expansive quarter of the city composed of many sub-areas that qualify as neighborhoods in their own right.” South Shore, like the other officially designated neighborhoods of Chicago, is just such an “expansive quarter.” Comprising three square miles, it has a population of roughly 50,000, down significantly from its high of 80,000.

The World Is Always Coming to an End alternates chapters of memoir with chapters of reportage and analysis. For many years, Rotella directed the American Studies program at Boston College, where he still teaches, and the book reflects that background. In 1999, at an Indian restaurant near the campus of Brown University, I overheard a young woman saying to her companion, “But what do they mean by ‘American Studies’?” Her conversation-partner, a fellow who looked several years older, answered in a very smug voice: “Everything . . . and nothing.” Me? I love a book that includes a discussion of the opening scenes in Raymond Chandler’s novel Farewell, My Lovely as received by the 12-year-old Rotella (loving the “virtuosity of Chandler’s language,” but puzzled by Moose Malloy’s “militant insistence on making a big deal about having a problem with black people”) alongside digests of city history and sociological analysis and conversations with twenty-first-century residents of South Shore.

Rotella’s mother grew up in Spain; his father, in the Italian community in Eritrea: “Franco’s air force and their German mentors did their best to kill my mother in Barcelona in the course of developing the art of destroying cities from above. The British air force had a go at my father in Asmara during the Second World War.” That partly explained their willingness to settle in South Shore in 1967 when the Hyde Park apartment building where they’d lived was scheduled to be torn down and replaced by a high-rise. Both Rotella’s parents were academics, working on their PhDs at the University of Chicago while teaching elsewhere, so South Shore’s proximity to the university was a big plus: “Black people moving in, white people getting out, excitable talk about a spike in crime, urban crisis, and decline—but not a peaked cap or a Stuka in sight.” Better yet, “the university had a lab school to which they intended to send their three young sons.” And they got their bungalow for a good price.

This brief mention of his parents’ taste of the world coming to an end, easily missed by a skimming reader or one flicking too hastily the Kindle screen, is characteristic of Rotella’s subtlety and his lapidary style, in which the virtues of literary prose and the discipline of magazine writing (at which he excels) complement each other.

I was going to tell you about Ava St. Clair and “Maurice” (as Rotella calls him here) and others in South Shore who, in these pages, represent the many-sidedness of the neighborhood, but it occurs to me that I have already given you more than enough to decide whether you’ll buy or borrow a copy of the book. If you do, you’ll have the pleasure of meeting them yourself; if not, your loss.

Postscript: A friend to whom I recommended Rotella’s book wrote to say that “out of nineteen Barnes & Nobles (the last old-fashioned book store available to most of us) within 50 miles of my (wealthy, well-populated) location, it is not in stock at a single one.” Of course, she could get it in a day or two from Amazon, and she could see a bit of it online before ordering, but she wouldn’t be able to browse in the time-honored manner before making up her mind. For her, and for others who may still be on the fence, I will quote from the concluding paragraph of the book.

Here’s the set-up: Rotella has been visiting the house on Oglesby where he once lived with his family. Now it’s owned by an African American couple, Darryl and Tonia, who bought it from the couple who bought it from Rotella’s parents. “Talking with Darryl on his deck,” Rotella writes,

I am revisited by a very early memory of a winter storm that caused an enormous tree limb to fall on the swing set that that once stood just about where I am now sitting. I woke up one morning to find an essential piece of my familiar landscape transformed into a fantastically compelling new hybrid structure of twisted metal and elaborately forking branches, all covered and surrounded by deep snow.

Rotella recounts the way he responded to this change (“I could feel myself growing stronger, . . . more subtle in my understanding of how to make a way through the tangle of things”), but then he concludes that underneath this altered environment and the “novel me” that adapted to it were “the persistent layers of what had been there before . . . I discovered that, though the world had changed and I had changed with it, everything was also still what it had always been.”

What a pitch-perfect conclusion! Quoting from it here feels like a transgression, as if I were giving away the ending of a novel, but maybe it will induce a few readers (including my friend) to get the book into their hands.

John Wilson is Contributing Editor for the Englewood Review of Books. His essays and reviews have appeared in Books & Culture, Christianity Today, First Things, Commonweal, The Christian Century, National Review, The Weekly Standard, the New York Times Book Review, the Wall Street Journal, the Boston Globe, and other publications. He and his wife, Wendy, live in Wheaton, Illinois, where they are members of Faith Evangelical Covenant Church.

If you enjoyed this review, be sure to subscribe to the quarterly print edition of FORMA Journal.